Learning Objectives

This is an intermediate-level course.

After completing it, mental health professionals will be able to:

- Identify

transference and countertransference as they manifest themselves in therapy.

- Describe the five

tasks and the self-monitoring function therapists must perform in order to use transference and countertransference benevolently.

- Formulate efficacious

transference and countertransference interpretations.

- Explain when, with

whom, and how frequently to use transference and countertransference

interpretations.

This course is based on the most accurate

information available to the author at the time of writing. Cognitive

psychology and neuroscience findings regarding brain development, structures,

and activities continue to shed light on what were once regarded as merely

psychoanalytic concepts and processes. Consequently, new information may

emerge that supersedes some explanations in this course.

This course may provoke disturbing

feelings in readers due to their unresolved conflicts, but it also gives them

information about processes by which they can resolve these conflicts.

Outline

- Introduction

- Manifestations of Transference and Countertransference

- Challenges Inherent in Identifying Transference and Countertransference

- Words: Therapeutic Material

- Words: Extra-therapeutic Material

- Vocal Bursts

- Feelings: Transferential

- Feelings: Countertransferential

- Dreams

- Fantasies and Daydreams

- Behavior

- Diagnostic and Interpretive Tasks

- First Task: Taking In Transferred Material

- Second Task: Holding and Permitting Regression

- Third Task: Decoding

- Fourth Task: Formulating Hypotheses

- Fifth Task: Verifying Hypotheses

- Overarching Meta-Function: Self-Monitoring

- Wording Transference and Countertransference Interpretations

- A Transference Interpretation

- A Countertransference Interpretation

- The Right Attitude

- Qualities of Effective TRIs and CTRIs

- Using Transference and Countertransference Interpretations

- Appropriate Versus Inappropriate Clients

- Timing

- Frequency

- Principles Underlying Guidelines for Using TRIs and CTRIs

- Final Thoughts

- Footnotes

- References

Introduction

Transference and countertransference can contribute to positive therapeutic outcome in non-analytic therapy as much

as in analytic therapy. They can also contribute to negative outcome and

treatment failure. If existential, cognitive-behavioral, or any other non-analytically

oriented therapists fail to notice these displaced phenomena at work in their

sessions, they are limited in their ability to help their clients move beyond

their one-sided perceptions of the problematic relationships and events they

experience both outside of therapy and in therapy. “Extant empirical work

supports” (Gelso & Bahatia, 2012, 388) this conclusion (Buchheim et al., 2017; Tmej et al, 2020; Antichi & Giannini, 2022).

If, however, therapists identify and

decode displaced material that manifests itself during therapy, they

can complement and/or correct clients’ perceptions. Then, as therapists share their insights and invite corroboration, clients can consider how what is transpiring in therapy is the result of their unresolved conflicts and explore appropriate ways of resolving them. Thus they can heal themselves and engage in wholesome relationships with others.

This course explores how transference and countertransference manifest themselves in subtle ways that therapists can learn to identify and use to enlighten clients regarding their contribution to their interpersonal difficulties. This course also teaches clinicians to identify the covert ways in which they are contributing to the interactions they are having with their clients. It also sensitizes clinicians to transcultural and intracultural mediators and moderators of transference and countertransference manifestations.

Finally, this course outlines the five tasks of diagnosing and interpreting transference and countertransference and clarifies therapists’ need to monitor their work as they perform these tasks. It helps them identify clients who will benefit from this interpretive work at appropriate times during their sessions.

This is the second course in a three-part series, based on Transference and Countertransference in Non-Analytic Therapy: Double-Edged Swords by Judith A. Schaeffer, Ph.D. (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2007).

The third course focuses on how to benefit from transference and countertransference love that arises in therapy.

(Note: To return to the course after clicking a footnote, click the Back button in your browser.)

Manifestations of Transference and Countertransference

Challenges Inherent in Identifying

Transference and Countertransference

Transference and countertransference

challenge therapists in at least three ways. First, because the conscious mind

cannot have direct knowledge of phenomena “residing” in the unconscious mind,

therapists can detect transferred material only in the vague, shadowy

signs of its presence. They can discover it only as it manifests itself in

words, feelings, dreams, fantasies, somatic responses, and behavior; as each of

“these voiceless and vociferous little parts of [the self] … do their best to

add their ‘two cents’ to the final product” (Wittig, 2002, 143).

Second, because manifestations of

transference and countertransference are a source of data but not a

source of evidence (Smith, 1990), therapists cannot simply take them at

face value. They suggest what is probably going on but cannot be used in

and of themselves to prove what is going on. Consequently, therapists

must “unpack” them for them to yield the information they hold. Especially

in the case of traumatized clients, Ogle and colleagues (2013) warn, therapists

must subject manifestations to decoding and interpretation.

Third, therapists must not forget that

transferred material is characterized both by similarities across cultures and

differences among and within cultures. Roles of women, for instance, are similar yet

distinctive in Islam and Christianity or in the eyes of adolescents versus senior citizens. Hence, therapists must attend to transcultural as well as

intracultural variables in order to discover the most likely meaning of transference

and countertransference phenomena.

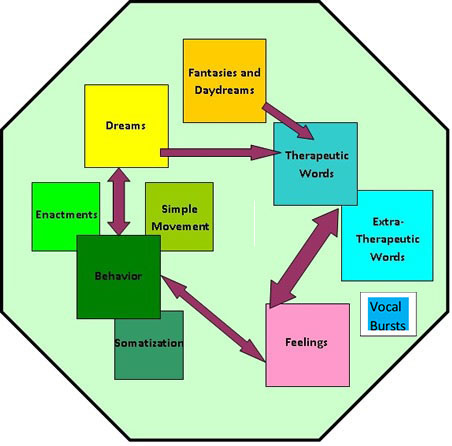

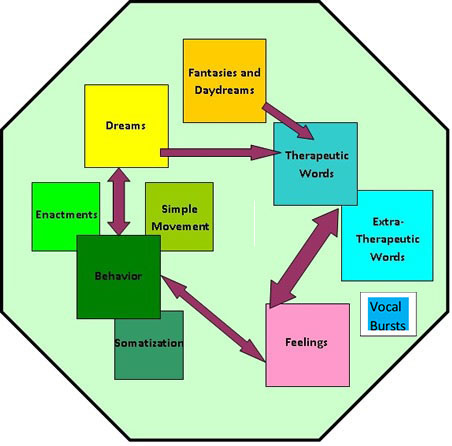

Categories of transference and

countertransference manifestations are artificial in one respect because they

overlap and merge. Emotions, for example, find expression in words, facial

expressions, gestures, and dreams even as dreams consist primarily of actions

taht evoke affect. Examining these categories separately, however, permits us

to simplify complex phenomena and create manageable templates that can be

placed over what transpires in and between therapy sessions.

Words: Therapeutic Material

Most therapists want to believe that the words clients use validly and reliably reveal the true nature of their problems and concerns. Thus therapists take these words at face value. They use their denotations or dictionary definitions.

However, many words with denotations clients consciously use to convey meaning also carry connotations or affective associations of which they may be unaware. Many convey meaning laden with subtle, emotional nuances. A client who says that she wants to work on her relationship with her father, for example, may simply mean her biological father. But she may also be unconsciously revealing her need to improve her relationship with others she associates with that man: those in authority, those who protect her, or those who are simply older and male. The client may even be referring to her older, noticeably self-confident, take-charge female therapist.

Similarly, a client who says, “I want to get rid of my depression” may mean “my sadness, loneliness, and listlessness.” But she may also be unconsciously referring to the depressing quality of her therapeutic relationship that closely resembles interactions with her self-centered spouse.

Thus therapists must be open to the possibility that connotation-bearing words that clients use are manifestations of transference. They are “messages” from the unconscious mind. They are Freudian “slips.”

Therapists should suspect the same of what they themselves say because the unconscious mind is always trying to find ways to move its contents into consciousness. Therapists unintentionally say what they consciously forbid themselves to say. “I am afraid I cannot schedule you next week,” for example, may be revealing therapists’ fear of what clients are about to share with them.

1

Words: Extra-therapeutic Material

Therapists intent on discovering transference must also examine the seemingly irrelevant material that clients introduce in sessions. At times, in referring to extraneous material, clients are consciously intending to shed light on their goals, give background material, or provide information about themselves. At other times, however, clients are unconsciously revealing the nature of their therapeutic relationship (Kahn, 1997). They might be trying to reveal what is hindering their progress in therapy.2

Despite the

client’s clearly stated goal to learn to be a better parent, she began her

second session by speaking of not being called back to substitute teach by a

local school. She wondered if she had not done a good enough job. Her

therapist, in turn, wondered whether his client was really asking about how

well she had done during her first session. Had her performance been good

enough for her therapist?

The therapist

remembered that his client had called that morning to ask about the roads.

Because heavy rains had made roads slick near her house, she wondered whether

he thought the roads near his office were dangerous. She really

wondered whether her therapist would call her again, so to speak, or be like

the school personnel. Was it dangerous to travel the “road” to therapeutic

work?

The therapist decided to test his hypothesis that the call the client made to him was due less to the weather than to her concern about his evaluation of their first session. He began the session by asking, “Did I seem disappointed in our session? Did you call to find out how emotionally dangerous it might be to come back?”

The client

breathed a sigh of relief and answered thoughtfully. Yes, there were

similarities between him and school personnel. He too was an evaluator who

might find her wanting. Yes, it felt dangerous to her to think of returning.

Subsequently, she

returned weekly, revealing in detail how her early years were marked by poor

grades for performance in the “book” of her father. Then she dealt with feeling

inferior as a parent and teacher.

As this vignette reveals, when talking

about a third party, clients may be displacing toward their therapist.

They may be unintentionally revealing their feelings about the person with whom

they are working and sides of themselves they might safely reveal during their

sessions.

Clients’ urge to do so – to reveal

self-in-relationship – is unusually strong in the closeness of the therapeutic

setting. For it is there that their unconscious desire to share what is really

important, but too threatening, most easily breaks through the barrier between

the conscious and unconscious minds. It is “intended” on an unconscious level.3

The client complained

bitterly of his religion teacher, saying how stupid and “out-of-it” she was. He

could not stand her or her class. His cognitive-behavioral therapist listened

attentively, waiting for an opportunity to help her client recognize the value

of doing his assignments for the class despite of his feelings toward his

teacher. Not doing homework and skipping class were the client’s presenting

problems. Though he was bright and capable, he was failing.

One morning, a frantic call from the client’s mother exposed his drug problem. He had been expelled from school for smoking marijuana, and it was not the first time. Realizing she should have decoded his hatred-for-his-teacher remarks much sooner, the therapist said, “You never even mentioned you were having trouble with drugs.” Her client looked painfully embarrassed but quickly shot back with, “I can’t talk to you about certain things. You’re too old. You don’t understand what it’s like to be me.”

Too late, far too late, had the client’s real message become clear. Had the therapist decoded the transferential meaning of his complaints about his teacher, she could have afforded him an opportunity to explore his belief that closeness in age was a prerequisite for trusting a person. Without that, he could only presume that his therapist was as much “out-of-it” as his teacher. He could not count on his therapist to understand his pain.

Especially noteworthy is extra-therapeutic material that clients bring in at the beginning or end of sessions. Seemingly unconnected to hardcore therapeutic work, it often holds important transferential messages.

He walked in

feeling very, very tired, saying he couldn’t get enough sleep. “Was he also

saying that he was very tired of therapeutic work?” his therapist wondered. Was

his therapist’s insistence on his becoming self-sufficient tiresome for him although it was his stated goal?

“Maybe,” the

client answered when asked about possible in-session fatigue. “I am tired of

people trying to change me,” he admitted. “It started back in grade school. The

teachers always had something hard for me to learn. It seemed it would ever

end.” Then, after a brief period of silence, he breathed a sigh of relief,

saying “Nobody ever cared about how hard it was for me before today.”

Subsequently he moved with uncharacteristic zeal into what he himself needed to

change.

Vocal Bursts

Transference can also be manifested in what

are called vocal bursts: “brief linguistic sounds that occur in between

[words] in the absence of speech” (Cowen et al., 2019, 699), such as sighs, gasps,

and laughs. These pre-language, trans-cultural vocalizations indicate some 13

emotions, including awe, disgust, contentment, and ecstasy. Thus therapists

identifying transference cannot afford to ignore them.

Feelings: Transferential

Transferential feelings are those

displaced to the therapist because of subtle similarities between the therapist

and persons outside of therapy. Clients whose parents were intolerant of them,

for example, may experience their therapist as intolerant because of displaced

feelings triggered by a “kernel of truth:” the therapist’s subtle but intolerant behavior.4

Though single, obvious feelings would not

appear to require decoding, what appears to be a simple feeling may indeed be an

emotional blend: a complex emotion with a second or even third feeling at the

periphery of the obvious one (Cowen et al., 2019). Anger due to a therapist

being slightly intolerant, for example, may include fear of the therapist’s

rejection and sadness because of it.

“She cancels for

so many reasons,” her therapist thought. Some seem legitimate, others flimsy. She

recognized that the material on which the client was working was embarrassing

for her, but she wondered whether their therapeutic relationship was even more of

an obstacle to her coming?

When her client

finally came for a session, the therapist listened and watched for displaced

material that might help her decode what on the surface appeared to be positive

feelings. She also opened herself to decoding her own countertransference:

annoyance that sessions were being cancelled and fear of a premature

termination.

Finally, when her

client described her mother-in-law as controlling and said she was going to set

firm limits with her, the therapist decided to use a transference

interpretation to ask if her client felt able to set limits during sessions.

Her client said that she wasn’t sure. Noting that ambivalence, however, the

therapist asked the client to explore possible negative transference. Subsequently, the

client stopped canceling sessions.

Recent research supports the theoretical

assumption that insight alone does not bring about behavioral change. “What is

ultimately required is the forging of affective conviction to cognitive

insight” (Hoglend & Hagtvet, 2019, 8). But theorists vary as to which of the

“24 dimensions of emotions that can be conceptualized in terms of emotion

categories” (Cowen et al., 2019, 708) are most crucial to change.

Theorists also disagree about which of the

“27 distinct varieties of reported emotional experience” (Cowen et al., 2019,

700) are most common in therapy. Racker (1972) tells therapists to expect first

what is nearest to consciousness. Clients want to bond with their therapist and

therefore hope to be found worthy of their therapist’s efforts. Beneath this

hope, however, can be fear of being judged.5

Other theorists tell therapists to expect

feelings most likely to contribute to the therapeutic alliance, regardless of

their closeness to consciousness. On the positive side are feelings of love,

calm, and relief resultant from experiences of unconditional acceptance by

others being transferred to the therapist who, in turn, provides unconditional

positive regard. But even these feelings might be coupled with fear of

unconditional acceptance becoming conditional.

On the negative side are feelings of

distrust of a therapist who appears too good to be true, fear of being engulfed,

sadness because of previous broken promises, embarrassment, shame, or a

combination of these feelings. All can be transferred from experiences with

others.

Because bonding experiences are at least

partly negative, primitive negative feelings can easily combine with each other

and with positive feelings. In fact, the earliest bonding experiences commonly

consist of a positive experience of having one’s basic needs met on demand,

followed by a negative one of learning one has asked too much and/or too often.

To

decode feelings, then, is to derive the true meaning of complex and fluctuating

emotions that originally appear to be simple and stable. It is to study body language

along with “tune, rhythm, and timbre in speech because they are the truest

indication of emotions” (Bostanov & Kotchoubey, 2004). It is to listen

carefully to reports of dreams and fantasies and to consider the connotation of

words clients choose. Most importantly, it is to note whether there are

contradictions between or among various manifestations of transference.

She came late,

saying that she had rushed to get to her appointment. She was unsettled,

overwrought, and uneasy. When her therapist asked about her rushing, she simply

explained that she had not left the house in time. The therapist then had to

decide whether to take at face value a poor judgment of time and distance or to

decode her client’s words as possible manifestations of transference.

Noticing her

client’s uptight body and clipped sentences, the therapist decided to ask

directly about whether leaving the house late might be connected to reluctance

to come to her appointment. She then received what was a far truer answer. Her

client said that she was not sure that the therapist could really help her.

A fruitful

exploration of the exact nature of their work and the relationship it implied

followed, during which it became clear to the therapist that the client was

transferring her disappointment with former teachers to her therapist.

Feelings: Countertransferential

Even as therapists decode transferential

affect, they must be alert for countertransferential affect, for it can reveal

both the interpersonal weaknesses of clients and the work therapists themselves

must do to facilitate therapeutic progress. Having had negative experiences

with teenagers, for example, therapists can feel demeaned by adolescents. They

can perceive them as crass and self-centered, even moments after they enter the

therapy room. When adolescents sense this unspoken attitude, they can become

self-conscious. They can then come across as crass in their anxiety-ridden reaction to a person who dislikes them. Others have disliked them and inflicted harm, which has taught them a lesson: “Harm others before they harm you.”

Especially challenging for therapists are

countertransferential feelings transferred by clients who cannot tolerate, own,

or even put them into language because they precede their ability to speak

(Modell, 1980). Like infants who deliver subliminal affect-laden messages

before they can use language, clients unconsciously hand over their

feelings of being unloved, blamed, or confused to their therapists. Thus, by

unconscious design, the truth about clients is discoverable first in the countertransference

therapists experience when with them. Then it is discoverable in the transference

their clients experience when their therapists give evidence of their countertransference.

As a rule, therapists first

discover the truth about themselves in emotional reactions that are excessive

or inappropriate for what their clients are sharing (Tower, 1956). These

feelings are much nearer to the heart of the matter than reasoning. Indeed, therapists’

unconscious, affect-based perception of their clients is amazingly accurate. Moreover,

it is in advance of the conscious, cognition-based conception of the

interpersonal situation therapists form (Heimann, 1950). Emotions are

experienced far faster than thoughts are formulated, according to neuroscientific

research (LeDoux, 2002; Pally, 2002; Schaeffer, 2007).

As a

rule, therapists’ behavior or somatic response reveals their feelings.

Sleepiness, for example, can indicate that therapists have felt abandoned by

clients who frequently intellectualize, speak monotonously, or talk in circles

(Racker, 1972).

She moved from

topic to topic as skillfully as a skater circles a rink, returning periodically

to certain issues but never completely dealing with them. Her therapist grew

increasingly sleepy but tried to convince herself that a warm room and

insufficient sleep was making her head feel heavy. She wondered, however, why

nothing she did, including getting up to adjust the shades, alleviated her

distress. “Should I be decoding” the therapist wondered, “because the client is

‘saying’ more than meets the eye?”

Finally, the

therapist decided to test her hypothesis that the client’s circling speech

might be unconsciously intended to disconnect from her therapist. “When you

circle from topic to topic, I simply can’t stay with you,” she said. “I get so

frustrated that I disconnect from you. Could it be that you want to disconnect

from me?” she asked.

“I don’t know,”

the client responded, “but I do know that this happens to me a lot. I’ve been

so hurt by people not listening to me. Even as a child, when I said I wanted to

play with other children, they never heard me. I need help with how to talk.

I’ve needed it forever!”

Thus, decoding a countertransferential

response proved invaluable in terms of “unlocking” painful affect and exposing

childhood experiences from which the client continued to suffer.

Similarly, therapists’ feelings can

indicate enactments in which they have already become embroiled (Hinshelwood,

1999). Therapists’ irritability, for example, may be in the service of staving

off guilt feelings for having already acted out their dislike of a client

(Schafer, 1997).

We will now take a closer look at therapists’ countertransferential feelings, grouping those most commonly experienced (Cowen & Keltner, 2020). We will then look at the rarely discussed feeling of envy.

Countertransferential Sadness

Countertransferential sadness usually

combines feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, helplessness, emptiness, depression,

and self-pity because of loss. Therapists’ depression, in particular, merits

special attention because it robs therapists of self-esteem and self-efficacy.6

Arlow (1985) claims that therapists’

depression is a countertransferential reaction: a defense against the

depression of clients. Clients come to therapy because of an unconscious sense

of a bad self even as they consciously proclaim a good self in relation to bad

others. Occasionally clients project a good self onto their therapist, but more

often it is a bad self (Epstein, 1977), which they subject to punitive measures

in unconscious imitation of prior caregivers (Racker, 1968). Therapists are

especially vulnerable to countertransference depression when treating

clients with Cluster B personality disorders (Betan

et al., 2005).

However, it must be acknowledged that

countertransferential depression also depends on therapists’ own sense of self.

Therapists with a positive sense of self and an internal “caregiver” are in a

favorable position to realize that their depressed clients are engaging in

projective fantasies which they must first resonate with, then soundly reject.

In contrast, therapists whose

self-definition is negative may unconsciously add self-punishment to negative

transference. Even worse, when therapists experience the combined force of

their inadequate internal self and their clients’ projections, they can lose their

capacity for rational, objective observation. They may never admit it to their

clients, but they “agree” intrapsychically that they are inadequate (Epstein,

1977), as the following vignette illustrates.

First the minister

came to therapy; then his son joined him. Their therapist, who had been

painfully humiliated by adolescent males, thought that in this instance she was secure. But

as the loose-lipped, surly adolescent attacked first his father and then other

members of his family, she had to admit that she was becoming increasingly

uptight. Soon afterward, the father appealed to the therapist to set limits but

still allow his son to express himself.

Feeling demeaned

when the son shifted his focus from people to the “stupid” therapy sessions

that he was being forced to attend, the therapist resorted to articulating what

she thought would be an acceptable agenda. People could express their feelings,

but feelings would have to be combined with discussion so that both father and

son could arrive at a solution they could both endorse.

In formulating the

plan, of course, the therapist was unconsciously attempting to lessen the

negative impact that the adolescent was having on her, even as she was

consciously steering the course of therapy from problem to solution. She was

determined not to succumb to the adolescent’s negativity. She would side with

the father in his need to get rid of it. She resolved that she would transform

the adolescent’s resentment into problem-solving energy and thereby reduce the

resentment she felt toward him.

Unfortunately,

this failure to address transference and countertransference issues proved

fatal. Imbibing his son’s attitude, as it were, the father began to align with

his son. He agreed that the family situation was so bad that it could not be

fixed and that therapy was a waste of time and money. The therapist was less skillful than she needed to be.

However, rather

than address her painful countertransferential feelings of inferiority and

impotence, the therapist again set out to convince the father, if not the son,

of the value of patience and hard work in therapy. She conveyed her hope that

things could change. As her own professional and psychological survival became

uppermost in her mind, she continued to act out – rather than decode – her

powerful countertransferential feelings.

Eventually, when

her agenda failed, the therapist admitted to herself that therapy was going

nowhere. She was incapable of reversing the negativity. She could no longer

count on her clinical expertise. When the father finally refused another

appointment, she merely mentioned her availability if he changed his mind.

Thus, the therapist’s insidious sense of

self-impotence and low self-esteem clouded her vision, which led her to

self-destructive despair. Her acting-in contributed to therapeutic

failure no less than did her own and her adolescent client’s acting-out.

Had she interpreted her depression to her clients, however, and asked whether

they, too, were experiencing painful feelings of inadequacy, victimization, and

resentment, it is likely that the father and son would have found her more like

them and thus more able to help them. They could have addressed the problem in

their therapy before, the problems they were dealing with outside of it.

Countertransferential Anger

As noted in the previous vignette,

countertransferential anger can include resentment toward abusive clients – if

not hatred of them – as well as disdain for victims of abuse combined

with revulsion and disgust for what happened to them. It manifests itself in

various forms of acting-out: withdrawing from clients (Plakun, 1998), becoming

irritable and restless because of precious time being taken up with what seem

relatively small problems, and even feeling bored or sleepy because of mundane

therapeutic issues. Countertransferential anger may also reveal itself as

therapists’ resentment of the emotional barrenness of clients’ communications

or helplessness and frustration (Cohen, 1952), all of which may induce

sleepiness.

Moreover, therapists’ extended frustration over lack of progress in therapy can produce countertransferential anger. This, in turn, can result in inattention, annoyance, and forgetfulness (Schwaber, 1990). Therapists treating clients with Cluster B personality disorders can be especially vulnerable to countertransferential anger (Bradley et al., 2005).

Countertransferential anger can also stem

from transferential guilt resulting from clients’ provoking their therapists

into acting angrily to appease their own guilt (Chused, 1992). On the

other hand, in response to aggressive transference, therapists may experience

subjugation and victimization. In time, however, even tolerant therapists feel angry

and vengeful (Racker, 1972). Then, if they try to relieve their distress

through subtle recrimination, they experience guilt.

At times, countertransferential anger can

also be provoked by clients’ rejection of a state of dependence that is being

“asked for” by therapists who assume the role of “savior” (Racker, 1972). At

other times, countertransferential anger can stem from therapists’ inability to

tolerate shame resulting from not living up to their clients,’ their

colleagues,’ and their own expectations (Winnicott, 1958). It can serve as a

defense against the experience of shame resultant from therapeutic failure

(Lewis, 1987).7

Ironically, countertransferential anger

can also be the result of therapists’ efforts to protect themselves

(Rothschild, 2000). It can be a response to having been threatened, hurt, or

scared.

Paradoxically, elevated anger, including

aggressive feelings, can be akin to a life force that can lead to

loving, hating, or both, as therapists continue to interact with their clients

(Winnicott, 1965). In turn, both hate and love can enliven therapists. They can

help them “to fix [themselves] in the world, to create a target for [their] own

feelings ….” (Becker, 1973, 144).

In sum, because anger is so intertwined

with other powerful emotions, it is a “given” in the course of therapeutic

work, regardless of therapists’ sincere desire to be benevolent. Ironically, countertransferential

anger can arise because of benevolent intentions.

Countertransferential Anxiety and Fear

Countertransferential anxiety, a response

to some internal stimulus (LeDoux, 1995), usually takes the form of therapists

feeling scattered and confused. They are unsure of relating to clients who

resemble others whom they have found difficult. They are uncertain of

therapeutic progress (Schafer, 1997).8

Countertransferential fear, in contrast, is a response to the environment. It makes therapists feel disconnected, disorganized, without control, feeling “like the floor [has been] taken out from under [them]” (Furlong, 2022, 20), and unable to think. This challenging condition tends to be a reaction to autistic clients (Gomberoff et al., 1990), attention deficit clients, hyperactive clients, or clients with Borderline Personality Disorders (Colli et al., 2014).

Countertransferential fear can also cause therapists to experience disequilibrium in response to schizophrenic or manic clients (Kantrowitz, 1997) or terror in the presence of clients with Antisocial Personality Disorders.

All of these experiences can result in

therapists’ desire to get relief by imposing their own ideas and solutions on

clients rather than patiently and painstakingly helping them discover at their

own pace what they must do to change.9

Therapists’ fear and anxiety can also

develop because they experience clients’ hold on them as an unconscious fear of

intimacy, seduction, engulfment, aggression, or dread of therapeutic regression

(Langs, 1979). Therapists may become apprehensive, for example, when clients

ask them for more time and attention than they can afford to give or feel comfortable giving.

Paradoxically, countertransferential

anxiety and fear may combine with guilt feelings and result in actions and

words indicative of submissiveness. This submissiveness, in turn, may cause

therapists to refer frustrating clients, to pamper those they do not refer, or

to search for quick resolution of complex situations to get relief

(Racker, 1972).

Countertransferential Gladness

Countertransferential gladness runs the

gamut from contentment to joy to elation. It may also manifest itself in

therapists’ feeling superior and wanting to boast (Handley, 1995) or to monopolize

the therapeutic conversation.

At times, countertransferential gladness

lures therapists into engaging in the unwholesome practice of competing with

their clients and their families or other professionals, such as medical

doctors or spiritual directors, in working with their clients. Therapists can

become insistent, for instance, that clients follow their advice rather than think

for themselves or consult others (Blum, 1986a).

However, the double-edged sword of

countertransferential gladness usually rekindles hope in clients and thus

proves extremely helpful. It contributes to the formation or repair of the

therapeutic alliance. But danger lurks even there, for gladness on the part of

therapists may induce in them positive feelings about therapeutic progress,

feelings that are unjustified because they rest on denial of still-needed,

difficult therapeutic work.

Countertransferential Envy

Because envy of clients is considered

shameful and unprofessional even when it is not acted out, therapists rarely

admit it. Unfortunately, however, therapists’ determination not to be outshined

by clients whom they envy at the same time that they help them is more common

than therapists would like to believe (West & Schain-West, 1997). Envy of

clients’ real accomplishments, or even of their potential to achieve, may lead

to therapists not supporting or encouraging their clients (West & Schain-West,

1997). Envy of clients may even result in premature termination if clients detect

therapists’ envy.

Identifying countertransferential envy

begins with becoming aware of the anxiety that accompanies it (Racker, 1968).

It includes being aware of the possibility of envy to morph into lack of joy

and satisfaction as therapists focus on their clients’ gifts rather than their

own.

Finally, envy might be operative if

therapists become verbose. They might be trying to prove they know more than

their clients.

Dreams

“There exists in us an internal stream of

intuitive knowing that is not in our conscious awareness. Paying attention to …

dreams lights a path, helping us know what we know and see what we see”

(Ferder, 2010, 86).

Dreams that clients bring into therapy are rich sources of

transference, especially if therapists are dream figures (Ferenczi, 1909). Therapists’ dreams are also valuable sources of countertransferential information if dream figures are clients (Tower, 1956). Jung, for one, found dreams he had about his clients to be crucial to his understanding of transference and countertransference, and to compensations he might be making because of poor attitudes toward some of them (Main, 2004).

Dreams are highly symbolic, containing

both primitive urges to act without regard to reality and rational motives for doing

so. They are often complicated, extended, and exceedingly confusing (Hedges,

2007). For they contain “clues about facets of [our] life that feel safe enough

to come out only in the stillness of the night” (Ferder, 2010, 86). Thus they are

worth extensive decoding.

Only an in-depth presentation would do

justice to the decoding of dreams, but the following vignette reveals the

value of doing so.

The therapist

noticed her client’s tight facial muscles and forced congeniality. She claimed

she was eager to work on assertiveness; but when her therapist began helping

her with specific assertive skills, she remained tense. It was only by decoding

her client’s dream that she learned what was really going on.

In the dream, the

client was being chased down narrow halls from one room to another. Wherever

she turned, doors opened into other rooms but never to the fresh, freeing

outside. The “enemy” chasing her was so close that she even felt its hot breath

down her back. The client thought that the narrow halls and rooms were those of

her own home. She thought that her critical, demanding husband was the “enemy”

always breathing down her back with his instructions. She couldn’t escape him.

She couldn’t get free.

While this interpretation may well have been accurate, the therapist

wondered about transferential implications. Could the rooms be the contents of

therapy sessions, which were packed with information but never let the learner

breathe freely and easily? Could the “enemy” chasing her be her therapist, whose

words felt like suffocating hot air? Could the client be feeling as if she were

being chased by a well-meaning therapist intent on doing good but nevertheless

robbing her of her freedom?

Sharing these

hypotheses, the therapist learned that her interpretation of the transference

was accurate. Had she not done this decoding, she would have never realized the

harm she was doing.

Fantasies and Daydreams

Fantasies are mental images created by

needs, wishes, or desires that occur during non-sleep states. Daydreams are

extended fantasies, even as fantasies are often “kernels” of daydreams. Though

both may seem simple, fantasies and daydreams are actually intricate, detailed,

and elaborate.

Fantasies and daydreams involve both

primitive urges and believable presentations (Herron & Rouslin, 1982). They

are means of accommodating to the environment, understanding what is occurring,

internalizing environmental events, and discharging energy from conflict

(Piaget, 1962). Hence, they can reveal transference and countertransference.

Furthermore, as fantasies and daydreams

bring ideals into reality, they become the basis for hopes and expectations in

interpersonal relationships. As ideals, however, they aid and abet

disappointment and dislike – even hatred – of real persons who inevitably fall

short of ideals. Yet fantasies and daydreams represent emotional “activity”

needing to be understood and worked on. They provide clues about clients’

emotional responses, including their reactions to their therapist (Herron &

Rouslin, 1982). Thus they call for decoding.

Unfortunately, clients seldom share

fantasies and daydreams with their therapists because they appear to be

distractions not worthy of attention. Consequently, therapists must be ever

alert to their presence, suspecting them in their own daydreams and fantasies

as well as in clients’ subtle movements and body language, particularly in

lapses of focused attention or mini-dissociative episodes. Clients whose eyes

become “glassy,” for instance, may well be daydreaming. Subsequently, they may

make reference to the heart of their reverie.10

One fruitful way of decoding fantasies and

daydreams is to look for the needs that they encode, particularly those that

can be met by others.

After a chance

encounter outside of the therapy office, the therapist found it difficult to

stop fantasizing about her client for several hours. “Strange,” she thought, “I

have so many other things going on.”

During

supervision, however, the therapist became increasingly aware of her positive

attraction to the client. His good looks, optimistic attitude, and refreshing

viewpoints made him “the perfect client.” “Still,” she asked, “why do I fantasize

about him?”

The therapist then

noticed subtle similarities between her junior high school crushes on

boys and therapy sessions with the client. She hypothesized that her positive

countertransference, related to her own need to enjoy those crushes, might well

be reflecting exactly what her client also needed to look at: the part he

played in sexual “rituals” that struck others as adolescent infatuation.

Indeed, her client had said that, though he disagreed, others said he was always flirting.

The therapist

worded her countertransference interpretation carefully during their next

session: “Could the thoughts I keep having about junior high days be

originating solely within me or are you contributing to them? They’re positive,

but would you say ‘out of place’ in our therapy sessions?”

The client was at

first bewildered. But when asked to take his time to respond, he realized his

attraction to his therapist, although he didn’t think that his feelings were

something that he could put into words. He never verbalized these kinds of

feelings, he admitted. He always tried to tell people that he liked them by

“just being himself.” “Could this be why people say I ‘flirt?’” he pondered.

Later, for the first time in his life, he dealt with behavior previously deemed

inconsequential.

Behavior

Manifestations of transference and

countertransference in behavior include body language, simple movement, complex

movement, and physical sensation. All are messages from unconscious to

unconscious through bodily means. “The body is the unconscious” (Pert, 1997, 141).

Indeed, “the basic units of experience are [not words but] bodily interactions

between self and others” (Fast, 1992, 449).

The behavior of the body contains key

information that determines exactly what clients and therapists are trying to

convey to each other (Scaer, 2005). Both are being

unconsciously influenced by a series of slight, even subliminal, signals.

Details of posture, gaze, tone of voice, and respiration are noticed and

recorded by both therapy participants (Meares, 2005).

Moreover, because the body cannot lie, it

is a source of truth about the present as it embodies memories of the past.11 The body has “the ability to tune in to the psyche: to listen to its subtle

voice, hear its silent music and search into its darkness of meaning” (Mathew,

1998, 185). Hence, in order to discover transferred material, therapists must

decode their own and their clients’ bodily behavior.12

Body Language/Simple Movement

Body language or simple movement refers to

inadvertent responses of the body to subtle, unconscious “messages” from the

right hemisphere. “You are in some kind of danger,” for example, is a common

message that makes clients fold their arms in front of them. However, when

asked, clients usually deny their fear, for the transaction that sent the

message from the brain to the arms was unconscious. Thus, it becomes extremely

important for therapists to study their clients’ and their own muscular

movements, postures, gestures, and other somatic reactions during therapy.

Of particular importance are right-hemisphere-controlled facial indicators, especially subtle movements around the eyes and mouth (Brownstein, 2007; Schore, 1994). For the left-hemisphere-controlled right side of the face, particularly the eye (Cowen et al., 2019), registers socially appropriate affective responses whereas the right-hemisphere-controlled left side, particularly the eye (Cowen & Keltner, 2020) divulges hidden personalized feelings (Mandal & Ambady, 2004).13

While what happens on a one-time basis may

not be worthy of much attention, body language that persists or repeats itself

is. For the unconscious mind produces again and again important material whose

overlooked messages need to break through to the conscious mind (Jung, 1946).

No matter what she

talked about, the client sat back in her chair, keeping a safe distance, as it

were, between herself and her therapist. “She has made progress, to be sure,

but could more be made?” her therapist wondered. “What needs to be done to

increase her comfort, if that is indeed a prerequisite for further work? Rather

than just space her sessions farther apart, I should address the sensitive

topic of our relationship and how it might be affecting her progress.”

During

the exploration that followed, the client reaffirmed her difficulty with

getting beyond the roles in which she had been cast as a child, roles so deeply

cultural that someone from outside her culture would hardly believe them. It

seemed as if the client needed to uncover the deterrents to changing her ways.

She had to trust someone who could understand how much she would be an exception

to her group if she changed.

“She sits back for

that reason,” her therapist decided, “She is telling me in body language how

alienated she feels.” So the therapist said, “It’s hard to trust someone from a

different culture, isn’t it? You and I might seem so different.”

To her therapist’s

relief, during the next session the client reported a shift in her attitude

toward making a change. She hadn’t made the change, she explained, but

she was planning it in detail. And she leaned forward when sharing her plan.14

Thus both therapist and client benefitted

from the close attention the therapist gave to transference and

countertransference being manifested in simple movements. Her noting her

client’s distancing, in particular, was crucial to her understanding her

client’s inability to trust a person from an often-abusive dominant culture

(Andersen & Przybylinski, 2012).

Complex Movement

In contrast to body language that encodes relatively simple messages, complex movement communicates several displaced feelings and story-like cognitions.

Complex movement occurs in both the mind and the body, according to recent research (Nardi et al., 2023). Thoughts and words become coercive actions loaded with emotion that usually relates to figures in the client’s or therapist’s early years. It is action dictated by a “script” never actually seen (Field, 1989), one most likely written between conception and eighteen months, when tone of voice, facial expressions, and gestures serve as primary means of communication (Meares, 2005).

Complex movement that puts transferred feelings and thoughts into action is usually called

enactment.15 It is the last step of “information processing that builds and exploits emotional databases of mind and brain” related to displaced material (Levin, 1997, 1136).

In carrying out transferential enactment,

clients assign to themselves and their therapist roles specific to past

experiences that have remained conflictual and thus carry heightened affect

(Schore, 2011). They “intend” to play a part and have their therapist play a

related one for various reasons, some of which might overlap.16 They are usually revisiting

the past in order to have it turn out better.

Alternately, clients may be unconsciously

testing with their therapist a pathogenic belief acquired in childhood

(Sampson, 1992), asking “Is that belief really true? Or will this person give

me reason to negate it?” Indeed, “during therapy, [clients] work according to

an unconscious plan to disconfirm their pathogenic beliefs by testing their

validity in the therapeutic relationship” (Gazzillo et al., 2019, 180).

Then, by closely monitoring their

therapist, clients hope for the evidence they need in order to substitute a

wholesome belief for one that is pathogenic (Silberschatz, 2005). The therapist

will have acted as “an implicit regulator of the [client’s] conscious and

dissociated unconscious affective states” (Schore, 2011, 84). “If therapists

pass their [clients’] tests, [clients] feel safer and frequently make progress

toward their healthy goals” (Gazzillo et al., 2019, 180).

Enactment of negative feelings and

thoughts is also called acting-out. Because it strains boundaries,

acting-out is considered a regressive interaction “experienced by either

[client or therapist] as a consequence of the behavior of the other”

(McLaughlin, 1990, 595). It must be quickly decoded and, if necessary,

examined, lest it limit the capacity for therapeutic work and exacerbate

extra-therapeutic interpersonal problems, for others soon find maddening the

“mind reading” required by someone acting-out. Clients must learn that others

greatly prefer words that describe feelings.

Meissner (1996) notes that “the potential

for countertransference difficulties to influence the therapist’s thoughts,

feelings, attitudes, and words is great enough. The potential for these unconscious

processes to find expression in the therapist’s … behavior and action is even

greater” (51).17

The same is true, of course, for

transferential difficulties influencing client’s behavior. In turn, on a

subliminal level, words used in therapy can become an incitement to action on

the part of both clients and therapists (McLaughlin, 1990). Both persons

unconsciously desire responses in themselves and others in line with their

transference and countertransference schema. Both want to “shape a happening,

bring about an enactment, in accord with [their] fears and hopes” (McLaughlin,

1990, 599). Both fear that the present might otherwise be simply a repetition

of the past. Both hope it will be improved, if not wholesome.

Countertransference enactment is often a

matter of therapists’ participating in the acting-out of clients’ transference.18 Therapists unconsciously collude with clients in mutual projective

identification organized primarily around clients’ unresolved conflicts

(Plakun, 1998). Thus, countertransference enactment conveys meaning regarding

clients’ transference conflicts (Sandler, 1976). Clients who are still

conflicted over wanting to be nurtured unconditionally and finding parental

figures unwilling to do so, for example, might fail to bring their copayment.

Should therapists refuse to play a parental role by asking instead for payment,

they will be actually addressing that conflict.

Countertransference enactment can also be

a matter of therapists’ own unresolved conflicts. Those with narcissistic

conflicts, for instance, might repeatedly insist that they are right (Wilson

& Weinstein, 1996). Those with aggressive conflicts might act belligerently.

Those with unresolved security conflicts might be dogmatic (Casement, 1991).

At other times, countertransference

enactment can be a matter of therapists attempting to counteract their own

weaknesses. Those who are indecisive, for instance, may exaggerate their

open-mindedness (Wilson & Weinstein, 1996).

An in-patient

adolescent ended his session by telling his therapist that another staff member

regarded her as incompetent. Unable to process her shame sufficiently, the

therapist set out to prove her competence. During a staffing two hours later,

she vigorously defended her client, blaming others for his bad behavior and

insisting on the soundness of her judgment. Unfortunately, exoneration was the

opposite of what her crafty client actually needed. He needed to take

responsibility for his behavior.

Impressed with the

therapist’s reasoning, however, the staff pardoned the client, who in time not

only repeated his misbehavior but took an even more adamant stand that he

should not be held responsible. He was the worse for his therapist’s erroneous

defense. He had been harmed by his therapist’s acting-out, a result of her

blindness to both his manipulating her and her own unresolved conflicts over

being thought incompetent.

Ogden (1994) thinks of countertransference

enactment as a powerful non-verbal “interpretation” being unconsciously

conveyed to clients. The “interpretation” may take a simple form, such as

ending a session early when stress levels are high. Similarly, instead of

asking for clarification, therapists may go off on a tangent when confused.19

Countertransference enactment has been

identified as an unconscious means of either indulging or punishing clients. By

indulging clients, therapists infantilize them: ask less of them than they are

capable of giving, provide for them what they themselves have the power to do

themselves, and absolve them of their obligation to change. By enacting rescuer

roles, therapists do clients the disfavor of not having them face their

dysfunctional patterns.

Therapists unwittingly indulge clients by “caressing”

them with words in order to quiet their own negative feelings. They speak in

soft tones or assure clients that all things are passing. They praise clients

for minor achievements that are more likely to be the result of chance than

hard work. Similarly, therapists try to divert clients from painful

countertransference-causing conflictual material by directing attention to

non-countertransferential material. By not addressing their own distress,

therapists spare their clients the pain of discovering their maltreatment of

others.

The therapist was

uneasy every time she met with her highly educated and wealthy client who had a

subtle habit of demeaning her. She did not want to admit this uneasiness,

however, either to herself or to him. Instead, she rationalized that she would

be noticeably prepared when her client came and thus prove herself his equal.

“Competition for outstanding performance is good for a person,” she said to

herself. “It makes people reach for the heights others have attained,” she

thought as she recalled seminars in which she felt inferior to male students.

Sessions appeared

to go relatively well as the therapist conveyed information the client

professed to want. On his termination form, however, he referred to a stifling

atmosphere in his sessions. There was an absence of free exchange, he wrote,

for his therapist seemed defensive. He couldn’t say that he felt disrespected,

but he knew deep down that mutual respect was simply not there. Rather, some

kind of a power struggle was going on.

Indeed, in a

primitive attempt to outdo one another, both therapist and client were

indulging each other on the surface but battling for superiority in the “deep.”

Sadly, by not addressing her countertransference, the therapist failed to help

her client deal with his dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors. In effect, she

punished him indirectly.

Punishing clients directly

includes discounting them. For instance, therapists can unconsciously perform

the exact opposite of roles clients’ assign. Plakun (1998) tells of a

previously victimized client assigning her therapist an abuser role. Instead of

exploring the client’s desire to be abused, however, the therapist spent the

time assuring the client that he was kind and caring. He would never abuse her.

In the course of doing that, of course, he was refusing to accept

countertransferential feelings of guilt. Thus he denied his client the

opportunity to work through her trauma related to being victimized.20

Alternative ways of punishing clients

include responding in a hostile, distant, frozen manner or taking a moralistic

stance that condemns clients. Therapists become excessively sympathetic to

third parties, for instance, and “take clients to court in a superior or angry

way” (Pick, 1985, 164). Alternately, they “forget” to bring up something

important, become highly distracted, or dissociate. Or they become silent,

whereby they strike a compromise between expressing their hostility and its rejection.21 They identify with a persecutor at the same time that they withdraw from that

identification (Racker, 1972).

In sum, whatever its unconscious

motivation, enactment is a psychic operation that is almost always related,

directly or indirectly, to the very reason clients enter into a therapeutic

relationship in the first place. It is also a psychic operation whereby

therapists unconsciously react to challenging aspects of their work with

clients. Dealing with it inappropriately mediates treatment failure (Plakun,

1998).

But dealing with it appropriately mediates treatment success, for it is usually the most authentic response therapists can make when unable to use words. It shows clients how they are affecting their therapist as well as those outside of therapy. It facilitates changing maladaptive relational habits (Shapira-Berman, 2022).

The client continued to think and act so narcissistically that her therapist was at his wit’s end. Verbal attempts to help her understand what she was contributing to her interpersonal difficulties had led nowhere. In fact, they motivated her to continue.

Finally, when his client rose to storm out of her session, her therapist also rose and spontaneously touched her client’s shoulders to stop her. Thwarted in her desire to leave, she yelled in protest. He said nothing for a few minutes, then spoke firmly but respectfully: “That’s enough. Be silent. Be quiet.”

At the end of their session, he was then able to say sincerely that he appreciated her cooperation and looked forward to their next session. His enactment had created a new reality, a new experience that became transformative as his client changed her overly self-focused habits.

Somatization

Yet another potential manifestation of transference is somatization: a source of truth known in the present but pertaining to the past. It is the body’s revelation of what happened earlier in the mind and “heart.”22 In fact, a growing body of research points to the importance of such phenomena

as intestinal flora and gut biome revealing one’s general sense of well-being

or lack thereof (Bach, 2019).

Similarly, recent neuroscience research reveals that experiences such as traumatization are recorded in the body on a cellular level (Van der Hart et al., 2006). Because of somatic changes in autonomic arousal, transference phenomena can be manifested in the body of a previously traumatized individual years after the trauma (Gene-Cos et al., 2016). An adult client’s smiling uneasily as she protests her love for her father, for instance, might be revealing negative experiences with him. For “implicit relational knowledge is not purely psychological but essentially psychobiological, mind and body” (Schore, 2011, 79).

Transference manifests itself in psychosomatic symptoms or illness aimed at drawing “the psyche from the mind to the original intimate association with the soma” (Winnicott, 1949, 254). Citizens of a country entered by immigrants, for example, can displace their concern about insecure national boundaries to their bodies in what is “roughly equivalent to the fear that [their] own body will be penetrated” (Lijtmaer, 2017, 692). Thus they experience heightened anxiety related to their belief that “racial minorities have the potential to ‘contaminate’ White Americans” (Tummala-Narra, 2019, 4).

Transference manifests itself in somatization because many unresolved conflicts occur in the pre-verbal period of life. Dealing with somatosensory information then becomes a major challenge to meaningful interpretation of its transference manifestations.

Somatization might be adaptive when it originally occurs, but it becomes maladaptive when ongoing because what is uncontrollable in early life usually becomes controllable due to development. It is adaptive to experience “butterflies” before being able to use language to manage anxiety, for example, but maladaptive to retain those physiological symptoms once reality testing reveals heightened anxiety is uncalled for.

Somatization in therapists, a twin of depression and a form of acting-in, is usually either a matter of thoughts stimulating emotions that then find bodily expression, or a matter of emotions themselves finding bodily expression. Like transferential somatization, countertransferential somatization manifests itself in symptoms and bodily conditions that have no physiological basis. Relatively common examples are sudden stabs of pain; tears; trembling; a growling stomach; strange sensations in the solar plexus; fits of coughing; poor sleep; sensitivity to noises; sleepiness, tightness, or tension, particularly in the chest (Chammas, 2023), throat, or jaw; nausea; rising heat; abdominal cramp; barely perceptible odors or tastes; and sexual arousal (Boyer, 1997).

“I am more than tired,” the therapist noted. “Most of my clients have been making progress. Why am I not relieved, even energized?”

It was only when some of her clients regressed significantly that she realized she was investing more energy in therapy than they were. One couple, for instance, became ambivalent about improving their relationship. Though they agreed they had to make personal changes, they resented having to make the effort. Furthermore, they revealed that they resented their therapist for saying so clearly that nothing else would save their marriage.

Being relatively sure of the countertransferential meaning of her fatigue, the therapist interpreted her countertransference in their next session. “I’m not sure why I am so tired after your sessions,” she said, “but could I be putting more into this work than you?”

“Now that you mention it,” the husband replied, “we are always being asked to account for what we did or did not do during the week. There’s more to life than doing therapy assignments!” After the conversation that followed, the couple finally began to take more responsibility for their progress. Slow but steady, their progress matched their own timetable rather than their therapist’s.

Indeed, it is crucial for therapists to stand in the spaces of different pieces of their self-experience and not use language too quickly, for words can never adequately substitute for bodily experience (Bromberg, 1991). Rather than telling clients what they think they know, therapists must listen to their clients and to themselves from an embodied place. To understand their clients’ displaced relational patterns, therapists must become aware of what they actually feel like in their own body (Looker, 1998).

In a fascinating article, Hedges (2007) gives a blow-by-blow description of how he used somatic countertransferential material when working with a client with a psychotic disorder, one who seemed extremely resistant to healing. After trying numerous other interventions, Hedges finally permitted himself to experience the client’s psychosis on a somatic level. “This is about me,” Hedges realized. “I have to let myself feel all of this” (23).

And he did. He then reported, “My mind swam in timeless … horror. I saw slaves being slaughtered and eaten alive by lions … tears welled up in my eyes. My stomach churned in violent upheaval. I stammered trying to speak what I was experiencing …. I had to rescue myself from the dizziness and emotional pull of the sadomasochistic pit …. I finally grasped at an experiential body level what [had] been perhaps [my client’s] deepest truth. … [My client] has for a lifetime feared relationships based on the template of a drugged and blinded cannibalistic scenario. He has experienced his emotional relationship with me according to the same pattern of abusive horrors” (Hedges, 2007, 23).

With this new countertransferential insight, Hedges (2007) was finally able to break the impasse he and his client had reached. “[My client] and I were together at last (23),” he wrote.

Damasio (1994) reminds therapists that somatization is common because emotions are actually conglomerates of sensations, which are integral experiences of the body. Each emotion has a different bodily expression, starting with a unique pattern of skeletal muscle contraction that is noticeable on the face and in body posture.

Each emotion also feels different on the inside of the body. Different visceral muscle contractions are discernible as body sensations that are automatically and involuntarily transmitted to the brain. Shame, for example, feels like heat rising in the face; sadness, like wet eyes (Rothschild, 2000).

Thus feeling of deadness in therapists might reveal how clients were neglected or loved and then rebuffed. Consequently, they never really experienced the vitality otherwise natural to infants (Field, 1989). Similarly, an inability to engage in deep breathing might reveal clients’ resistance to processing their emotions.

Hence, the next section is devoted to the important tasks therapists must perform in order to make transference and countertransference work for – not against – them and their clients

Diagnostic and Interpretive Tasks

In order to identify, decode, and

interpret transference and countertransference, therapists must involve their

non-verbal right brain as much as they do their verbal left brain. This is

because transference and countertransference, like most relational transactions,

rely heavily on client-therapist cueing and responding that occur too rapidly

for simultaneous verbal exchanges and conscious reflection (Lyons-Ruth, 2000).

The right brain, the repository of unconscious material, must assist the left

brain, the repository of conscious material.

Besides using both hemispheres, therapists

must slow down their mental activity enough to perform five distinct but

interwoven tasks. All the while, they must monitor themselves closely in order

to decide how well they are performing each task and when they should move from

one to another. They must also integrate the tasks in order to accomplish their

main goal of interpreting transference and countertransference.

First Task: Taking In Transferred Material

Therapists perform the task of taking in

transferred material by making a conscious decision to continue to take in what

they suspect they have already taken in unconsciously, namely manifestations of

clients’ transference; and reacted to unconsciously, namely manifestations of

their own countertransference. This first task requires therapists to

deliberately open themselves up to what they sense they have already opened up to on an

unconscious level: conflictual contents of their own unconscious minds

attempting to enter their conscious minds.

Thus, the first task is a matter of

therapists trying to “be there” for clients and themselves in a new way (Heath,

1991). It is a matter of forming a composite picture of conscious and

unconscious information from which therapists and their clients can, in time,

derive authentic meaning.

The first task is fundamentally an acknowledgement of the nature of the human mind: it allows us to not only survive but also to thrive if—and only if--the conscious and unconscious minds work together. As Locke and Latham (2019) explain so well, the unconscious looks to the conscious mind for direction, but so does the conscious mind look to the unconscious for assistance as it struggles to navigate the real world. They can and do get each other “on board.”

Remember that the processes by which

therapists receive unconscious material from their clients and themselves,

namely transference and countertransference, operate first on an unconscious

level. Without knowing it, therapists receive the affective, cognitive, and

sensate messages their clients displace. Without intending it, therapists react

to subtle messages from the recesses of their own unconscious mind. At the same

time, they unconsciously transfer material to their clients.

When therapists perform the first task,

they intentionally “make room” for displaced material in their conscious minds.

They choose to increase their awareness of the feelings, attitudes, fantasies,

dreams, images, thoughts, sensations, and behaviors that they and their clients

are transferring (Bird, 1922). Therapists open themselves to a state of

“convergence” of past and present. They attend to their own unconscious

behavior as a possible sign of countertransference, asking whether they “are

playing an active role in one of [their client’s relationship] dyads” (Carsky

& Chardavoyne, 2017, 400). Thus they offer to clients their “entire

availability.” They give them all the time and mental space they need in order

to deal with their still-unresolved conflicts (Grinberg, 1997). In fact, the deliberate reception of transference begins a process whereby

therapists acquire the intuitive empathy necessary for the therapeutic

alliance.

In performing the first task, therapists

take seriously their professional responsibility to regard transferred material

as central to therapeutic reality (Deutsch, 1926). They become congruent with

the painful, unconscious memories of their clients (Vanaerschot, 1997).

By deliberately increasing their awareness

of what their clients are transferring, therapists also bring to consciousness

their own countertransference. They take note of the roles they are

unconsciously assigning clients as well as those their clients are

unconsciously assigning them. Therapists who are assigned a parental role for

clients working through early child-parent conflict, for example, deliberately

“accept” an image of themselves as a controlling, self-indulgent parent.

Similarly, if they themselves are assigning the role of unruly children to

their clients, therapists hold in focus the emotional satisfaction they have

begun to experience from subjecting a child to their will. They allow

themselves to note in detail the muscle tightness of one who is immobilizing

another, albeit in fantasy.

To

summarize, the first task is one of adding latent or suggested content to

manifest or obvious content. Therapists combine clients’ unconscious body

language and meta-language with what they consciously say. They also add their

own unconscious perceptions and desires to conceptions and intentions of which

they are already conscious, or which they at least suspect. Therapists allow

right-brain learning to augment left-brain learning. They open themselves to

receiving non-verbal communication that cannot be put into words.

Second Task: Holding and Permitting Regression

The second task requires therapists to

hold the transference and countertransference they have received, often for

more than one session (Bion, 1961). It also requires them to allow the

regression that tends to occur in a deepened and broadened holding environment.

The use of regression in this

context is an extension in meaning of a word originally reserved for an

unconscious process. Strictly speaking, unconscious regression cannot become

conscious. However, the process of willingly entering into a regressive state

so resembles doing so unconsciously that no better terminology has been found.

Regression

enables therapists to embrace the full impact of their clients’ displaced

reality. “This is the clear, sharpened, whole message my client is giving me,”

therapists come to realize as they hold various manifestations of transference

(Smith, 2000).

Therapists perform the second task by

containing and autoregulating their own negative states long enough to act as

affective regulators for their clients (Schore, 2003b).23 In turn, their clients become aware of their therapist’s successfully managing

the distressful feelings, sensations, and thoughts that they have transferred

to him or her. Benefitting from their therapist’s work, clients sense that they

can survive the anxiety that has kept these conflicts from reaching

consciousness. They can finally heal because their therapist is sharing their

“burdens.” As Wilkinson (2003) claims so rightfully, a safe

holding environment is the most potent vehicle for healing.

Casement (1991) describes this affect

regulation as therapists’ refusal to follow their natural inclination to

disengage from the distressful transferential communications their clients

send. They refuse to use words, for they tend to have the unintended result of preventing in-depth understanding from taking place (Miller, 2022, 24).

Rather, therapists avoid closure, tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty, subject

themselves to “total immersion to establish contact” (Bach, 2019, 6), and

permit lack of differentiation in order to share their clients’ displaced

relational experiences (Schore, 2003a). They do not return to their

clients prematurely what their clients project to them (Joseph, 1978). They

renounce their own need for gratification.

In performing the second task, therapists

refrain from taking refuge in words. They resist their impulse to shift into a

left-hemispheric dominant state and respond verbally to clients’ verbal

messages. Instead, they hold sensations evoked by unconscious communication

(Stark, 1994) and sustain the countertransferential feelings that transference

triggers. They stay in the right hemisphere, which has a “wait and see” mode of

processing (Federmeier & Kutas, 2002).

Thus, therapists do for clients what

clients were unable to do for themselves at the time of an original conflictual

experience. They allow psychic pain to remain in their conscious mind.24

As they remain open and mute, therapists

observe their clients’ posture, gestures, and movements, taking note of the

tone, syntax, and rhythm of their speech. Therapists allow their own felt sense

to act as a body-based perception of meaning (Bohart, 1993).25

For

the sake of understanding through experiencing, therapists permit

themselves to contain their clients’ unresolved conflicts in their own bodies

(Kernberg, 1987). They endure the disturbing thoughts, feelings, and sensations

their clients put into them.26 In more cases than not, they let clients use projective identification to

transform them into someone “bad,” someone deserving of disrespect, even abuse

(Gorney, 1979). They let themselves feel that unwanted label on a bodily level.

The second task also requires therapists

to re-experience the breadth and depth of their own unresolved conflicts,

phenomena that constitute a key element in any countertransference response

(Kernberg, 1975). Therapists willingly suffer the painful countertransferential

thoughts, affect, and sensations that reflect their clients’ conflicts (Roth,